About the Case

Date: October 14, 1886

County: Autauga

Victim(s): Harry Kirk, Ben Fort, Abram Hinton

Case Status: attempted

In October 1886, news of three Black arsonists from Pickens County circulated in newspapers throughout the country. From Georgia to Michigan, it was the same basic story: three unnamed Black men burned down a house but soon were caught, jailed, and lynched by a mob of avenging whites. No press provided much information about the men or their supposed crime, though they did offer plentiful descriptions of their punishment.[1]

In October 1886, news of three Black arsonists from Pickens County circulated in newspapers throughout the country. From Georgia to Michigan, it was the same basic story: three unnamed Black men burned down a house but soon were caught, jailed, and lynched by a mob of avenging whites. No press provided much information about the men or their supposed crime, though they did offer plentiful descriptions of their punishment.[1]

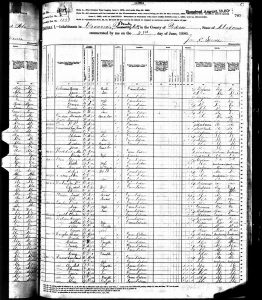

When researching the deaths of the unknown three Black men, we found virtually nothing at first. Our first big clue came to us from the St. Louis Globe Democrat, where a “Mrs. Amos Ball” was mentioned as the victim of the alleged arson.[3] “Amos Ball” was the first name we had encountered, and so we turned our attention towards him. On Ancestry.com, Ball was found in an 1880’s Census record, and from there a new and more detailed story began to form. Ball was a white farmer and due to Ball’s occupation and his neighbors listed as farm workers, we deduced that Ball was fairly wealthy.[4]

Concerning the three unknown Black men, we found nothing until we located a microfilm copy of small, local newspapers from 1886 in West Alabama. Using these local presses we identified the names of the three victims and began to reconstruct their lives and deaths. The West Alabamian reported that three Black men — Harry Kirk, Ben Fort, and Abram Hinton — allegedly broke into Mr. Ball’s home because of a rumor that Mr. Ball was stashing a large sum of cash. However, they did not find any. Allegedly, they stole groceries, blankets, supplies and a pistol before setting fire to his home. Soon after, they were taken into custody and sent to the jail in Carrolton.[5]

On October 14th, 1886, Kirk, Fort, and Hinton were taken from the Carrolton County jail by a mob of seventeen masked men. Their jailer, Sheriff Chapman , was reportedly “deceived” by the mob and forced to give up the three prisoners.[6]

The lynching occurred earlier than the October 21st date that had been reported in newspapers across the country. After Kirk, Fort and Hinton’s arrest, an article naming the three black men as the alleged arsonists appeared in the Wednesday, October 13th, issue of The West Alabamian. The next issue, published on October 20th, reported that Kirk, Fort and Hinton had been lynched “last Thursday”,[7] which was the day after the October 13th issue was published. Some reports of the crime state the three men were hanged on a “neighboring tree”[8] and while other reports claim the three victims were hanged in a “graveyard.”[9]

According to the 1880 U.S. Census, Amos A. Ball lived on Franconia Road in Carrolton, Alabama. Ball’s neighbors were mostly black farm laborers. The census also listed Harry Kirk, Ben Fort, and Abram Hinton as farm laborers in the same community. They were most likely working for Amos A. Ball. The 1880s Census suggests that Harry Kirk, Ben Fort and Abram Hinton had possible relatives working on Ball’s farm. Their names were listed as Rose Kirk, Frank Hinton and Amanda Fort. The listed women and children may have been relatives of Harry Kirk, Ben Fort, and Abram Hinton.[10]

Franconia Road, where Amos A. Ball’s home was located, was approximately 6.9 miles from the Pickens County Jail. The nearest cemetery to the Pickens County Jail is Oakhill Cemetery, which is around 10 miles from the jail, which also happens to be along Franconia Road.

Significantly, an article published in The West Alabamian after the lynching stated it was committed out of a communal anxiety based on the fears that their ‘homes were not safe.’ Yet no other articles documented break-ins or arsons in the year 1886. The article reflected a passive admonishment of the lynching , stating that the county had juries “fully competent enough to deal with such crimes” and that the lynching was an “unfortunate affair sprang out of the conviction of the people that their homes were not safe.”[11] The article offered no further details about the lynching other than to say that incidents of alleged arson and theft were frequent.[12] The article seemed more like a representative statement of the county than an investigative source. The article acts as a public testimony for Pickens County, reasoning that the use of lynching in Pickens County was both a deterrent of black crime and a soother of white fears.

When we started this project, we were apprehensive. For about a month, our efforts yielded few results. We had few names, if any, and no information about the three murdered Black men from Carrolton accused of arson. Their names were lost and we knew we had to find them. Their murders were unsolved, their names unrecoverable, their place in history dehumanized. It was like they died two deaths, the first at the end of a rope and the second being their simple disappearance from any historical record.

We chose our thumbnail carefully . We had just found their out their names after nearly four months of research and with very few details. We spent the first month attempting to collect all duplicate articles reporting that the lynching had occurred. We felt like we were searching in the dark. The Equal Justice Initiative, the leading authority on mass lynchings, could only find a few articles reporting that this mass lynching even happened. Finding the identities of these murdered Black men was a milestone for our group and our class. After months of finding a few hits and getting a lot of misses we finally came across who they were. Without their names, the entire mystery of not only who they were but the circumstances surrounding their deaths would have been forgotten. The soil sample jars at EJI memorializing these three deaths are currently labeled as Unknown. These jars can now bear the actual names of the victims — Harry Kirk, Ben Fort and Abram Hinton. While their bodies are gone, their names can live on and inspire hope in those seeking to honor those who were victims of racial terror.

[1] The Baltimore Sun. 22 Oct. 1886

[3] St. Louis Globe Democrat. 22 Oct. 1886

[4] United States Federal Census. 23 Jun. 1880

[5] The West Alabamian. 13 Oct. 1886

[6] St. Louis Globe, Democrat. 22 Oct. 1886

[7] The West Alabamian,. 20 Oct. 1886

[8] Galveston Daily News. 21 Oct. 1886

[9] St. Louis Globe Democrat. 22 Oct. 1886

[10] United States Federal Census., 23 Jun. 18806

[11] The West Alabamian, No Title. 20 Oct. 1886

[12] The West Alabamian, No Title. 20 Oct. 1886