About the Case

Date: July 16, 1917

County: Pickens

Victim(s): Poe Hibbler

Sex of Victim(s):male

Case Status: confirmed

On Monday, July 16, 1917, Poe Hibbler (also known as Joe Hibbler[1]), a young black man was lynched in Pickens County, Alabama, most likely near Speeds Mill Road, just outside of Carrollton, Alabama. Hibbler was born around 1898, in Preston, Alabama, so he would have been about 19 years old at the time of his death.[2]

The local press initially stated that Poe Hibbler had been arrested on account of “rumors of a negro getting in trouble out near[3]” the home of a “prominent citizen” named Jim Price, a white man.[4] This “trouble” later came to be described as attempted sexual assault upon Price’s 15-year-old daughter, Inez Price.[5] Several sources documented the alleged incident. Hibbler apparently attempted to sexually assault Inez Price in her bedroom. As he entered her room, however, she woke up and screamed, frightening Hibbler away.[6] While in flight, “he was tracked to[7]” nearby Reform, Alabama by Jim Price.

The local press initially stated that Poe Hibbler had been arrested on account of “rumors of a negro getting in trouble out near[3]” the home of a “prominent citizen” named Jim Price, a white man.[4] This “trouble” later came to be described as attempted sexual assault upon Price’s 15-year-old daughter, Inez Price.[5] Several sources documented the alleged incident. Hibbler apparently attempted to sexually assault Inez Price in her bedroom. As he entered her room, however, she woke up and screamed, frightening Hibbler away.[6] While in flight, “he was tracked to[7]” nearby Reform, Alabama by Jim Price.

Price found Hibbler and another black male, who was never named and brought them to the closest jail, in Reform. There Price asked the Deputy Sheriff to bring them to Carrollton, the county seat, to be put on trial. The other black man, like Hibbler, faced charges of attempted sexual assault. The Deputy Sheriff, Jim Gunter, told Price that he would have to initiate a warrant against Hibbler and the other unknown black man in order for the Sheriff to be able to move them to Carrollton. Therefore, the men formally accused the two men of attempted rape. With the necessary procedural formalities in place, the Deputy Sheriff proceeded to move the men to Carrollton, but while he was en route, a group of “masked men[8]” apprehended the party on the side of the road. They told Gunter to let them have Hibbler, and to do what he pleased with the other man. Unfortunately, there was no other information given as to why the men wanted only Hibbler. The masked men then took Hibbler into the woods, while Gunter continued on his way towards Carrollton and placed the unknown man in jail. The unknown man was put on trial within the next few days, either the following Tuesday, July 17th, or July 23rd.[9] He was acquitted.

On Tuesday morning, July 17th, Poe Hibbler was found hanging from a tree “on the edge of the road[10]” by a “jury” made up of men from Pickens County. They determined that Hibbler had died from “strangulation with a rope at the hand of an unknown party or unknown parties.[11]” Hibbler was then buried in the “county poor farm[12] ”, possibly Haynie Cemetery, which is located off of County Road #7, (Turnipseed Road), in Gordo, Alabama. The location of this cemetery is approximately a quarter of a mile north of Alabama Highway 86.[13]

The full name for Jim Price, the prominent citizen who made the initial complaint against Hibbler, is likely James B. Price.[14] James Price was a landowning citizen who lived just outside of Reform, Alabama, where Poe Hibbler was initially brought into the jail. He had a wife and several children, one of which was a daughter named Inez Price. Inez Price was born around 1903.[15] Because Inez Price and Poe Hibbler were close in age, it possible that the two young people might have been involved in a romantic relationship. Given the harsh social stigma against miscegenation, and the fact that it was illegal in Alabama, the prospect of an interracial relationship may have motivated Price to end it violently. Additionally, if Price wanted to conceal a possible connection between his daughter and a black man, this might have given him a reason to bring in the unnamed black male with Hibbler. The inclusion of the unidentified male made it appear less likely that Hibbler and Inez Price had a consensual relationship. Instead, the two men together violated her against her will. If word got out that there had been only one black man who engaged in relations with Price’s daughter, it would be more likely that the daughter had entered into that relationship willingly. This could further explain why Hibbler was taken from the Deputy Sheriff while the unknown man was left alone and later acquitted and released from jail.

The full name for Jim Price, the prominent citizen who made the initial complaint against Hibbler, is likely James B. Price.[14] James Price was a landowning citizen who lived just outside of Reform, Alabama, where Poe Hibbler was initially brought into the jail. He had a wife and several children, one of which was a daughter named Inez Price. Inez Price was born around 1903.[15] Because Inez Price and Poe Hibbler were close in age, it possible that the two young people might have been involved in a romantic relationship. Given the harsh social stigma against miscegenation, and the fact that it was illegal in Alabama, the prospect of an interracial relationship may have motivated Price to end it violently. Additionally, if Price wanted to conceal a possible connection between his daughter and a black man, this might have given him a reason to bring in the unnamed black male with Hibbler. The inclusion of the unidentified male made it appear less likely that Hibbler and Inez Price had a consensual relationship. Instead, the two men together violated her against her will. If word got out that there had been only one black man who engaged in relations with Price’s daughter, it would be more likely that the daughter had entered into that relationship willingly. This could further explain why Hibbler was taken from the Deputy Sheriff while the unknown man was left alone and later acquitted and released from jail.

In addition to our research of Poe Hibbler, we also researched a supposedly separate lynching of an unidentified black male. This lynching happened on July 17, 1917, in Reform.[16][17] We believe that this lynching was actually the same event as the Hibbler lynching. Throughout our research, we found that most sources listed the date of Poe Hibbler’s lynching as July 23, 1917.[18] This date, however, is incorrect. The earliest article we found that announced Hibbler’s lynching was from the Pickens County Herald. This article was published on July 20, 1917.[19] Therefore, it would have been impossible for Hibbler to have been lynched on July 23rd. This article stated that Hibbler was lynched on a Tuesday night.[20] The date which the article was published, July 20th, 1917, was a Friday, and so the preceding Tuesday night would have been July 17th — the same day that our second lynching victim was supposedly lynched. The Pickens County Herald article also stated that a jury met on the day which followed Hibbler’s lynching, a Tuesday, July 17th. Because of this, we believe that Hibbler was actually killed on Monday night, July 16th. Additionally, another article from the Atlanta Constitution mentioned an unidentified black male who was lynched because he “confessed to entering the home of a farmer named Price earlier in the night[21]”. This was presumably the same Price whose house Poe Hibbler allegedly entered. This article was published on July 17th. Therefore, we feel confident in our assertion that the unidentified black male who was supposedly lynched on July 17th was the same man as Poe Hibbler. Additionally, because this article was published on July 17th, we have further evidence to support the assertion that Hibbler was killed on July 16th, not July 17th.

[1] 1910, U.S. Census, Preston, Sumter County, Alabama, p. 13B, Enumeration District: 0132, roll T624_33.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Negro Hung by Unknown Parties Near Reform,” Pickens County Herald (Carrollton, Alabama), 20 July 1917.

[4] “Two Negroes Lynched For Drawing Pistols,” The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia), 1917, 25 July 1917.

[5] 1920, U.S. Census, Reform, Pickens County, Alabama, p 15A, enumeration district 78, roll T625_38.

[6] “Two Negroes Lynched For Drawing Pistols,” The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia), 1917, 25 July 1917.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Negro Hung by Unknown Parties Near Reform,” Pickens County Herald (Carrollton, Alabama), 20 July 1917.

[9] “Two Negroes Lynched For Drawing Pistols,” The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia), 1917, 25 July 1917.

[10] “Negro Hung by Unknown Parties Near Reform,” Pickens County Herald (Carrollton, Alabama), 20 July 1917.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Haynie Cemetery in Carrollton, Alabama – Find A Grave Cemetery,” Find A Grave Cemetery, accessed 15 December 2017.

[14] 1920, U.S. Census, Reform, Pickens County, Alabama, p 15A, enumeration district 78, roll T625_38.

[15] 1920, U.S. Census, Reform, Pickens County, Alabama, p 15A, enumeration district 78, roll T625_38.

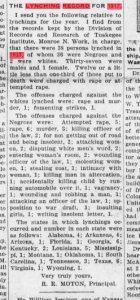

[16] “Report of the NAACP for the Years 1917 and 1919,” NAACP Maryland, January 1919.

[17] Studio, August, “MWT – Explore the Map – Lynching acts of white supremacy,” Monroe Work Today, Accessed 13 December 2017.

[18] “Report of the NAACP for the Years 1917 and 1919,” NAACP Maryland, January 1919.

[19] “Negro Hung by Unknown Parties Near Reform,” Pickens County Herald (Carrollton, Alabama), 20 July 1917.

[20] Ibid.

[21] “Negro Is Lynched By Mob In Alabama,” The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia), 15 Oct 1920.