About the Case

Date: September 15, 1893

County: 1782

Victim(s): Paul Hill, Polk Archer, Will Archer, Ella Fant

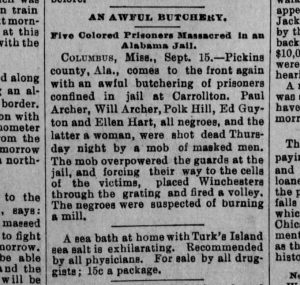

Only a few weeks after the lynching of Joe Floyd in August 1893 near Carrollton, Pickens County experienced another racially-motivated killing early in the morning on Wednesday, September 13th. This time, four African Americans accused of arson — Paul Hill, Polk Archer, Will Archer, and Ella Fant — were shot in cold blood in their Pickens County jail cells by a mob of masked men.

Only a few weeks after the lynching of Joe Floyd in August 1893 near Carrollton, Pickens County experienced another racially-motivated killing early in the morning on Wednesday, September 13th. This time, four African Americans accused of arson — Paul Hill, Polk Archer, Will Archer, and Ella Fant — were shot in cold blood in their Pickens County jail cells by a mob of masked men.

Initially five black victims had been reported as lynched but subsequent research revealed that four were killed. It was originally believed that Ed Guyton was a lynching victim but a local Pickens County paper, the Alabama Alliance News, claimed otherwise in a series of reports. Confirming the paper’s assertion was the 1900 Census, which listed Ed Guyton as a resident of the county.[1]

In February of 1893, the gin house and mill that Joseph Edward Woods was renting went up in smoke.[2] Woods was a white resident of Yorkville and a former private in the Confederate Army.[3] The details of the event were mostly provided by Guyton, who would become the lead witness for the prosecutors seeking the death penalty of the alleged arsonists. As such, the veracity of his claims should be carefully weighed; his testimony would literally save his life. It also may have been coerced.

According to Ed Guyton and as reported in the Alabama Alliance News, Polk Archer, Will Archer, Paul Hill, and Ella Fant connived to rob Woods of his crops and then later burned his mill and gin house to cover their tracks.[4] Guyton claimed that he was on his way to Ella Fant’s house to mend her shoes when he overheard the plot to rob J.E Woods. The four found out and forced him at gunpoint to participate in the robbery. He swore that they had stolen thirty bushels of shelled corn, a barrel of meal, and a bale of cotton. Guyton then claimed that he was able to escape the robbery while it was in progress, sprinting to Mr. Woods’ house to raise the alarm and then helping Woods attempt to save the buildings.[5]

Guyton feared for his life after the arson. He maintained that the other four repeatedly harassed him and threaten him not to go to the authorities.[6] He said that this threat, combined with the authorities suspecting him of committing the act or at least participating in it, eventually moved him to confess everything and avoid punishment.[7] He didn’t confess, however, until shortly after he was arrested along with the others.

Upon their arrival to the Pickens County Jail, Guyton and the four alleged arson suspects were set for a grand jury hearing with a bail of $500, which they were not able to pay. Their testimony was scheduled to be heard in court on Wednesday, September 13th. The lawyers claimed that their clients were unconstitutionally sent to prison. They backed up this claim using a letter that Guyton supposedly wrote while imprisoned that implied he had made the story up. Judge Oscar McKinstry presided over the case and ruled against the motion, stating that Ed Guyton had “rigidly adhered to his (original) statement,” referring to his original description of the arson and his forced involvement.[8] Guyton later claimed that he was forced to write the letter by his cellmates otherwise where they would have “strangled him in his cell while he slept”. Colonel M. I. Stansel represented the state in this case and Willett Hodo and J. B. Stansel represented the defendants. Extensive cross-question of witnesses led to a longer trial than expected.

Upon their arrival to the Pickens County Jail, Guyton and the four alleged arson suspects were set for a grand jury hearing with a bail of $500, which they were not able to pay. Their testimony was scheduled to be heard in court on Wednesday, September 13th. The lawyers claimed that their clients were unconstitutionally sent to prison. They backed up this claim using a letter that Guyton supposedly wrote while imprisoned that implied he had made the story up. Judge Oscar McKinstry presided over the case and ruled against the motion, stating that Ed Guyton had “rigidly adhered to his (original) statement,” referring to his original description of the arson and his forced involvement.[8] Guyton later claimed that he was forced to write the letter by his cellmates otherwise where they would have “strangled him in his cell while he slept”. Colonel M. I. Stansel represented the state in this case and Willett Hodo and J. B. Stansel represented the defendants. Extensive cross-question of witnesses led to a longer trial than expected.

At two o’clock in the morning of September 13, Wednesday, Sheriff John Tyler Hamiter was awakened with a firm knock on the jail door and a voice claiming that there was “officer with a prisoner transfer.” According to the Alabama Alliance News, Hamiter walked outside with his keys in hand.[9] Six masked men armed with rifles quickly disarmed him and marched him back to the jail where another 30 masked men had now gathered.[10] Sheriff Hamiter later testified that the intruders entered the jail and went straight up to the second floor, where the male prisoners were kept. There they shot to death Paul Hill, Polk Archer, and Will Archer while they huddled in their cells. They descended to the ground floor and shot Ella Fant to death in her cell. The mob now freed Ed Guyton and told him to leave town. The mob then dispersed “methodically” into the night. The Alabama Alliance News also reported that the public well in Carrollton had its thick rope cut and taken away on the night of the killing, possibly suggesting that the mob originally planned on hanging the four prisoners.[11] Paul Hill, Polk Archer, Will Archer, and Ella Fant were all buried at the County Poorhouse Graveyard outside of Gordo.

In its main article covering this lynching, the Alabama Alliance News offered a mixed review of the event. On the one hand, it declared the act evil.[12] But it also legitimated the rule of mob law if the public feared justice was not being properly served. Indeed, when seeking to understand the lynching it blamed the slow judicial process. “Our laws are too technical, and our judges, some of them, regardless of their oaths and all that, in too many instances depart from plain common justice, and offer as an excuse for this some fine, hair-splitting point of law – maybe to show their wisdom and possibly to defeat justice.” Then the newspaper delivered its own verdict on the fairness and proper use of lynching’s. “But, be that as it may, the fact remains that in too many instances the guilty go free while the innocent are made to suffer. Hence, we say we believe the growth of mob law, and it is on the increase all over the country, is due in a large part to the distrust of the law and the courts.”[13] This “slow pace” can be interpreted to mean the fair trial of black Americans. Many white southerners at this time, tragically, preferred to see a mob lynch a black person than see him or her go through a trial in the courtroom.

[1] 1900 Federal Census. Pickens County, AL.

[2] “Butchered in Jail: An Alabama Mob Kills Five Prisoners in their Cells,” Savannah Tribune (Savannah, Georgia), 23 September 1893.

[3] Alabama Civil War Muster Rolls. (1865). Joseph E. Woods. AncestryLibrary.com

[4] “Bloody Tragedy: Four Negroes Shot to Death by Mob of Citizens at the County Jail,” Alabama Alliance News (Carrollton, Alabama), 18 September 1893.

[5] “Bloody Tragedy: Four Negroes Shot to Death by Mob of Citizens at the County Jail,” Alabama Alliance News (Carrollton, Alabama), 18 September 1893.

[6] New York Times. Negro Prisoners Lynched. 16 September 1893

[7] “Bloody Tragedy: Four Negroes Shot to Death by Mob of Citizens at the County Jail,” Alabama Alliance News (Carrollton, Alabama), 18 September 1893.

[8] “Bloody Tragedy: Four Negroes Shot to Death by Mob of Citizens at the County Jail,” Alabama Alliance News (Carrollton, Alabama), 18 September 1893.

[9] “Bloody Tragedy: Four Negroes Shot to Death by Mob of Citizens at the County Jail,” Alabama Alliance News (Carrollton, Alabama), 18 September 1893.

[10] “Bloody Tragedy: Four Negroes Shot to Death by Mob of Citizens at the County Jail,” Alabama Alliance News (Carrollton, Alabama), 18 September 1893.

[11] “Bloody Tragedy: Four Negroes Shot to Death by Mob of Citizens at the County Jail,” Alabama Alliance News (Carrollton, Alabama), 18 September 1893.

[12] “Bloody Tragedy: Four Negroes Shot to Death by Mob of Citizens at the County Jail,” Alabama Alliance News (Carrollton, Alabama), 18 September 1893.

[13] “Bloody Tragedy: Four Negroes Shot to Death by Mob of Citizens at the County Jail,” Alabama Alliance News (Carrollton, Alabama), 18 September 1893.