About the Case

Date: June 30, 1894

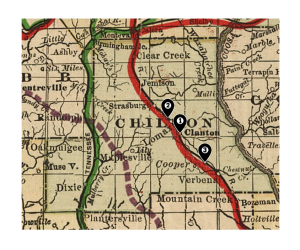

County: Chilton

Victim(s): Lewis Bankhead

Sex of Victim(s):male

Case Status: attempted

Lewis Bankhead

June 30, 1894

Cooper, Alabama

Lewis Bankhead, a 23-year old black man, was lynched in Cooper, Alabama, at the Louisville and Nashville (L. & N.) train station on June 30, 1894. After his capture, he was hanged from a tree and shot by a mob who left “his body filled with bullets.”[1] He was accused of sexually assaulting Minnie Jones,[2] a 12-year-old white girl. Her father was a farmer and commonly referred to as being Bankhead’s employer at the time of the alleged assault. His name is given as both James Jones[3] and Fletcher Jones.[4] White newspapers gave few details about the alleged crime, instead focusing on Minnie who was left “horribly injured, and … in a precarious condition.”[5] After assaulting Minnie, Bankhead reportedly traveled to Lomax, a nearby town, and attempted to assault another young white girl, but he was scared off by her screams.[6] The previous fall, Bankhead had been accused of attempting to assault another white child near Clanton, Alabama, in Chilton County. He was found not guilty. In light of the apparent attack on Minnie, the townspeople were unwilling to risk sending Bankhead to trial again and took matters into their own hands.[7]

Using information from the 1880 census[8] and an arrest record from 1889,[9] we know that Lewis Bankhead was born in either 1870 or 1871 in Tennessee. At the age of nine, he was living with his grandparents, Hiram and Edie Bankhead, in the town of Waterloo in Lauderdale County, Alabama.[10] His grandfather, Hiram, worked on a farm he didn’t own while his grandmother, Edie, kept the house in which the family lived. Interestingly, the 1880 census indicates there were many black Bankheads living in the surrounding area, suggesting that Lewis grew up surrounded by other family members.[11] There is a good possibility that Lewis was convicted of attempting to “ravish” (or rape) on September 14, 1889 in Lauderdale County, Alabama at the age of eighteen.[12] This was prior to when he was accused of attempted assault in Chilton County and found not guilty. At the time of his arrest; he was a farmer and was not married.[13] He was released July 14, 1893, eleven months before he was killed.[14]

When looking into what happened to Lewis Bankhead on the day he was killed, old white newspapers were the most helpful source of information when seeking to reconstruct the chronology of events. Newspapers.com, a national database, also provided leads to articles that offered a sense of the the white public perspective was on this event. These articles typically portrayed Bankhead as a “fiend” and “assaulter” and deserving of his fate. Ancestry.com was the most useful source when it came to securing leads on sources beyond white newspapers.

Despite the many newspaper articles that we have found detailing the events of the lynching, we are still left with many questions. We still do not know exactly what happened on the day Lewis Bankhead was killed. We cannot find what happened to Minnie Jones after she was supposedly assaulted. Chilton County did not begin keeping probate records until 1908 so there is little possibility of finding either the birth record for Minnie Jones (if she was even born in this county) or the death record for Lewis Bankhead. Additionally, while we have a general idea of where the L. & N. Cooper’s station was located, the structure no longer exists today, making it difficult to pinpoint where exactly Lewis Bankhead was killed. Another question we have is how to explain his apparent change of family status in the 1880s; his was listed as having a family in the 1880 Census[15] but as having no family in the court record in 1889.[16] Also, how and why did he end up in Chilton County in Central Alabama in 1894 after spending the majority of his life in Lauderdale County in Northern Alabama? We were unable to find anything regarding his lynching in any black newspapers, but if anything could be found in the future, that could give a whole new perspective to what happened June 30, 1894 in Cooper, Alabama.

All the newspaper sources we have are white newspapers. According to them, local whites grew in fear of Bankhead after he was not convicted for his previous alleged assault attempt on another white child. Only after his lynching did the white community breathe easier and feel that, “All is quiet in the neighborhood now”[17]. However, Chilton County would be the site of more lynchings in the future, suggesting that racial tensions bubbled for years. It is important to remember Lewis Bankhead today because he is not just a number in lynching statistics. He was a person and everyone deserves to have their story remembered accurately and compassionately. By telling the truthful and horrifying history of lynching in the United States, we can gain a better understanding on the roots of racism that still exist in this country today.

While Lewis Bankhead’s story may never be fully uncovered, it is vital to remember him as something more than a murder statistic. Knowing lynching victims on a more personal level adds an emotional component to the history previously missing in teachings. I felt a connection to the three men our group researched despite how little we truly know about their lives. I cannot walk out of this class after finals and forget everything I learned. By feeling this unique connection to the three victims, I know I will never forget their names and their stories. Looking at the thousands of lynchings that happened in the United States, I can only imagine the trauma black Americans faced seeing other black men and women being lynched. It is horrifying how many people witnessed lynchings, yet so many of the victims remain nameless and their stories died with them. Without doing my own research, I would have no idea the depths white people went to erase lynching and its victims for history. My determination to find out about that day in Cooper on June 30, 1894 not only led me to view the past from a new perspective, but to see American society today in a new light.

[1] “Another Negro Lynched,” The Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, UT), July 1, 1894.

[2] “Another Negro Lynched,” The Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, UT), July 1, 1894.; “Negro Lynched in Alabama,” The Indianapolis Journal (Columbus, IN), July 1, 1894.; “Cooper: A Young Negro Fiend’s Wild Career Cut Short,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), July 1, 1894.; “Colored Man Hanged: Charged with a Terrible Crime and Identified, He Is Summarily Punished,” The Inter Ocean (Chicago, IL), July 1, 1894.; “Hanged to a Tree: A Negro Fiend Lynched and Riddled With Bullets,” The San Francisco Call (San Francisco, CA), July 1, 1894.; “Swift Vengeance on a Negro,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), July 1, 1894.; “Criminal Notes,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Seattle, WA), July 1, 1894.; “Hanged On a Tree and His Body Riddled With Bullets: A Mob’s Summary Execution of an Alabama Negro: His Crime an Assault on a Farmer’s Little Daughter- Guilty of the Same Offense Before and Afterwards – Pursued by Infuriated Posses – Identified by His Victim – Criminal News,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, MO), July 1, 1894.; St. Joseph Gazette-Herald (St. Joseph, MO), July 1, 1894.; “Dealt Justice Themselves: Negro Ravisher in Alabama Lynched By a Mob and Filled With Bullets,” Louisville Courier Journal (Louisville, KY), July 1, 1894.; “Another Negro Lynched,” The Daily Sentinel (Grand Junction, CO), July 2, 1894.; “Promptly Lynched.: A 12-Year-Old Girl Assaulted by a Negro in Alabama,” Morristown Republican (Morristown, TN), July 7, 1894.; “Hanged to a Tree: A Negro Fiend Lynched and Riddled With Bullets,” The Morning Call (San Francisco, CA), July 1, 1894.

[3] “Promptly Lynched.: A 12-Year-Old Girl Assaulted by a Negro in Alabama,” Morristown Republican (Morristown, TN), July 7, 1894.

[4] “An Alabama Negro Lynched,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat (St. Louis, MO), June 30, 1894.

[5] “Cooper: A Young Negro Fiend’s Wild Career Cut Short,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), July 1, 1894.

[6] “Dealt Justice Themselves: Negro Ravisher in Alabama Lynched By a Mob and Filled With Bullets,” Louisville Courier Journal (Louisville, KY), July 1, 1894.; “Negro Lynched in Alabama,” The Indianapolis Journal (Columbus, IN), July 1, 1894.; “Colored Man Hanged: Charged with a Terrible Crime and Identified, He Is Summarily Punished,” The Inter Ocean (Chicago, IL), July 1, 1894.; “Hanged On a Tree and His Body Riddled With Bullets: A Mob’s Summary Execution of an Alabama Negro: His Crime an Assault on a Farmer’s Little Daughter- Guilty of the Same Offense Before and Afterwards – Pursued by Infuriated Posses – Identified by His Victim – Criminal News,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, MO), July 1, 1894.; “Doings in Alabama: Carefully Collated From Authentic Sources For Our Readers,” The Shelby Sentinel (Calera, AL), July 5, 1894.; “Doings in Alabama: Carefully Collated From Authentic Sources For Our Readers,” The Journal-Tribune (Gadsden, AL), July 6, 1894.; “Doings in Alabama: Carefully Collated From Authentic Sources For Our Readers,” The Progressive Age (Scottsboro, AL), July 6, 1894.; “Doings in Alabama: Carefully Collated From Authentic Sources For Our Readers,” The Pine Belt News (Brewton, AL), July 10, 1894.; “Doings in Alabama: Carefully Collated From Authentic Sources For Our Readers,” The Eutaw Whig and Observer (Eutaw, AL), July 12, 1894.; “Town Items,” The Banner (Clanton, AL), July 7, 1894.

[7] “Dealt Justice Themselves: Negro Ravisher in Alabama Lynched By a Mob and Filled With Bullets,” Louisville Courier Journal (Louisville, KY), July 1, 1894.

[8] Year: 1880; Census Place: Waterloo, Lauderdale, Alabama; Roll: 17; Page: 14D; Enumeration District: 141.

[9] Alabama Board of Corrections. County Convict Records, 1931–1948. 13 boxes [containing bound volumes]. Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama.

[10] Year: 1880; Census Place: Waterloo, Lauderdale, Alabama; Roll: 17; Page: 14D; Enumeration District: 141.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Alabama Board of Corrections. County Convict Records, 1931–1948. 13 boxes [containing bound volumes]. Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Year: 1880; Census Place: Waterloo, Lauderdale, Alabama; Roll: 17; Page: 14D; Enumeration District: 141.

[16] Alabama Board of Corrections. County Convict Records, 1931–1948. 13 boxes [containing bound volumes]. Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama.

[17] “Hanged On a Tree and His Body Riddled With Bullets: A Mob’s Summary Execution of an Alabama Negro: His Crime an Assault on a Farmer’s Little Daughter- Guilty of the Same Offense Before and Afterwards – Pursued by Infuriated Posses – Identified by His Victim – Criminal News,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, MO), July 1, 1894.