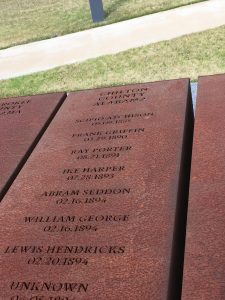

About the Case

Date: May 9, 1885

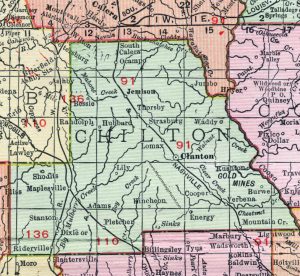

County: Chilton

Victim(s): Scipio Atchison

Sex of Victim(s):male

Case Status: attempted

Scipio Atchison

May 09, 1885

Dixie, Alabama

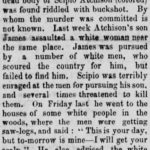

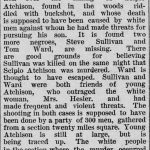

May 9, 1885, about 300 white men shot Scipio “Sip” Atchison in Dixie, a small farming community in Chilton County, Alabama.[1] He was a black man accused of threatening to kill white people in the town because his son, named either James or Sam Atchison, had been recently accused of raping a white woman named Emma Hesler and now faced the possibility of being lynched by local whites.[2] Scipio supposedly went through Dixie telling white residents that, “this is your day but tomorrow is mine. I will get your scalps.”[3] Recognizing that his own life was now in danger, Scipio fled only to be quickly caught by a white mob who left his body “riddled with buckshot” in the woods near the train station, Dixie Station.[4]

Emma Hesler was twenty-two years old at the time of her alleged rape and her husband, Martin Hesler, was thirty-one years. Based on the 1880 census, the Heslers lived in the Dixie area and were not wealthy or prominent. They could not read and write. Martin was listed as a farmer and Emma a housekeeper. They had twins, a son and a daughter, who were about seven years old at the time of the supposed crime.[5]

There is very little information available on Scipio and his family. They do not appear on the 1880 census. However, there is a land document from the Homestead Act that granted a person whose race is not listed named Sip Atchison a 109-acre section of land in Chilton County so it is probable that Scipio owned land and was a farmer.[6] Scipio’s wife is mentioned in multiple accounts in white newspapers, but only in passing. Several newspapers mention her finding Scipio’s body after attending services at a black church the day after he was killed.[7] The Selma Times wrote she was crying outside of a “negro church” near Dixie because she had heard gunshots and screams in the woods near her house the night before and feared the worst for her husband. She supposedly “knew” Scipio was dead because the white people in the area had been looking for him and that he had entered and not returned from the same woods she had heard the gunshots in. It is also reported that she did not trust the local police officers to ask them to help recover his body. She went instead to the home of a local doctor, T.M. Callier, for help searching for Scipio’s body.[8]

Multiple articles mention a second black man being found lynched with Scipio but whether this actually happened is unclear.[9] His name was Steve Sullivan and was reportedly thirty-five years old at the time of the possible killing. He was friends with Scipio’s son, and like Scipio, was also accused of making threats against the white people in the town.[10] However, a black man with the name Steve Sullivan is found in the 1900 census for Chilton County and a death certificate for him exists from 1915.[11] So, it is likely he was not lynched at the same time as Scipio. According to the 1880 census, Sullivan was a farmer in the Dixie area and he was married to Peggy Sullivan who was a house keeper and was thirty years old at the time. They were both literate and had three young children who were about eleven, nine, and six at the time of their father’s death.[12]

Most of the information about Scipio’s murder was located in various white newspapers published across the United States in May 1885. These articles made Scipio look guilty and deserving of his death. Most sources used language that characterizes Scipio and his son as being dangerous and animalistic, commonly using words like “scoundrel” and “fiend.”[13] Every newspaper assumed Scipio’s guilt. None of the papers mentioned that he was only accused of making threats against the white community.[14] The Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum in Calera, Chilton County provided some information on trains that ran through the area, however, they did not have any information that was useful for Scipio’s case. Dixie no longer exists and is now part of Stanton in Chilton County.

Scipio Atchison’s story is important to remember today because neither he nor his loved ones received any type of justice. I think it’s important to study people like Scipio because their stories have gone untold for far too long and their lives remind us that humans always deserve better treatment. Scipio’s life is part of a hidden history that obscures past racial injustices in America; this hidden history still exists because we don’t like to address issues that make us feel uncomfortable. Tragically, Scipio’s life was not uncommon. Many blacks at the time lived in fear and were at constant risk of being falsely accused of crimes they did not commit. When they were falsely accused they were not given the opportunity to prove their innocence. Whites at the time were normally assumed innocent until proven guilty. This was a privilege that black people were not given at this time and they’re often not given today. Unfortunately, this still occurs today in disproportionate numbers to black people in the United States.

[1] The Weekly Wisconsin, May 13, 1885; “The Dixie Excitement,” The Times-Argus, May 15, 1885; “An Alabama Alarm,” Memphis Avalanche, May 13, 1885, 28 edition; “Fears of a Negro Insurrection,” St. Paul Daily Globe May 14, 1885.

[2] “Fears of a Negro Insurrection,” St. Paul Daily Globe May 14, 1885; “Riddled With Bullets”, The Weekly Advertiser, May 19, 1885; “The Dixie Excitement,” The Times-Argus, May 15, 1885.

[3] “Riddled With Bullets,” The Weekly Advertiser, May 19, 1885.

[4] Der Deutsche Correspondent May 13, 1885; “Fears of a Negro Insurrection,” St. Paul Daily Globe May 14, 1885

[5] 1880 U.S. Census, Chilton County, Alabama, population schedule, p. 28 (stamped), dwelling 253, family 262, Martin and Emma Hesler; digital image, Ancestry.com, accessed Dec 4, 2019, http://ancestory.com.

[6] 1883 U.S. General Land Office Records, Montgomery County, Alabama,Document Number 2786, Accession Number AL4620_ _.098, Township 20-N, Range 12-E, Section 12 Sip Atchison; digital image, Ancestry.com, accessed Dec 4, 2019, http://ancestory.com. The Homestead Act granted plots of land to individuals, including free people of color.

[7] “Dead Body Found,” The Times-Argus, May 15, 1885.

[8] “Dead Body Found,” The Times-Argus, May 15, 1885.

[9] “Cause for Trouble in Chilton County-Facts in the Case,” “The Matter Largely Sensational,” The Weekly Advertiser May 19, 1885; The Memphis Daily Appeal May 14, 1885.

[10] “Trouble Which Arose From an Outrage”, The Austin Weekly Statesman May 21, 1885; “An Alabama Alarm,” Memphis Avalanche, May 13, 1885, 28 edition.

[11] 1900 U.S. Census, Chilton County, Alabama, population schedule, p. 01 (stamped), dwelling 16, family 16, Steve and Peggy Sullivan; digital image, Ancestry.com, accessed Dec 09, 2019, http://ancestory.com.

[12] 1880 U.S. Census, Chilton County, Alabama, population schedule, p. 38 (stamped), dwelling 354, family 365, Steve and Peggy Sullivan; digital image, Ancestry.com, accessed Dec 09, 2019, http://ancestory.com.

[13] “The Matter Largely Sensational,” The Weekly Advertiser May 19, 1885; “The Dixie Murders,” The Linden Reporter, May 22, 1885.

[14] The Eufaula Daily Times, May 13, 1885; St. Landry Democrat, May 23, 1885.

Featured Sources | |

|---|---|

|

An Alabama TragedyType: Newspaper “An Alabama Tragedy.” Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), May 12, 1885. |

|

Fears of a Negro InsurrectionType: Newspaper “Fears of a Negro Insurrection.” St. Paul Daily Globe (St. Paul, MN), May 14, 1885. |

|

Lawlessness in AlabamaType: Newspaper “Lawlessness in Alabama.” The Indianapolis Journal (Indianapolis, IN), May 13, 1885. |

|

The Matter Largely SensationalType: Newspaper “The Matter Largely Sensational.” The Weekly Advertiser (Montgomery, AL), May 19, 1885. |

|

The Recent Negro Killing at Dixie Station- Excitment and AlarmType: Newspaper “The Recent Negro Killing at Dixie Station- Excitment and Alarm.” Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), May 13, 1885. |

“Trouble Which Arose From an Outrage.” The Austin Weekly Statesman (Austin, TX), May 21, 1885.

“The Recent Negro Killing at Dixie Station- Excitment and Alarm.” Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), May 13, 1885.

“The Matter Largely Sensational.” The Weekly Advertiser (Montgomery, AL), May 19, 1885.

“The Father of a Rapist Quieted.” Memphis Daily Appeal (Memphis, TN), May 13, 1885.

“The Dixie Murders.” The Linden Reporter (Linden, AL), May 22, 1885.

“The Dixie Excitement.” The Times-Argus (Selma, AL), May 15, 1885.

“Riddled With Bullets.” The Weekly Advertiser (Montgomery, AL), May 19, 1885.

n.t. The Eufala Daily Times (Eufala, AL), May 19, 1885.

n.t. The Weekly Wisconsin (Milwaukee, WI), May 13, 1885.

n.t. The Livingston Journal (Livingston, AL), May 21, 1885.

n.t. The Eufaula Daily Times (Eufala, AL), May 13, 1885.

n.t. The Milan Exchange (Milan, TN), May 23, 1885.

n.t. St. Landry Democrat (Opelousa, LA), May 23, 1885.

n.t. The Magnolia Gazette (Magnolia, MS), May 22, 1885.

n.t. The Grenada Sentinel (Grenada, MS), May 23, 1885.

“Murders in Alabama.” National Tribune (Washington, DC), May 21, 1885.

“Lawlessness in Alabama.” The Indianapolis Journal (Indianapolis, IN), May 13, 1885.

“Found Dead in the Woods: Father of a Ravisher Punished for His Actions.” The Atlanta Constituion (Atlanta, GA), May 12, 1885.

“Fears of a Negro Riot.” Savannah Morning News (Savannah, GA), May 13, 1885.

“Fears of a Negro Insurrection.” St. Paul Daily Globe (St. Paul, MN), May 14, 1885.

“Excitement at Dixie’s Station.” The Indianapolis Sentinel (Indianapolis, IN), May 13, 1885.

“Ein Drohender Raffenfamyi in Alabama.” Der Deutsche Correspondent (Baltimore, MD), May 13, 1885.

“Cause for Trouble in Chilton County-Facts in the Case.” Memphis Daily Appeal (Memphis, TN), May 14, 1885.

“Associated Press.” Memphis Daily Appeal (Memphis, TN), May 13, 1885.

“An Alabama Tragedy.” Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), May 12, 1885.

“An Alabama Alarm.” Memphis Avalanche (Memphis, TN), May 13, 1885.

“A Colored Man Murdered.” New York Times (New York, NY), May 12, 1885.